feature

Improve Efficiency, Quality, and Comfort with ASHRAE Guideline 36

ASHRAE Guideline 36 gives specifying engineers a chance to deliver a better project specification but only if they pay attention to the details and communicate them to the project team.

Consulting engineers, construction contractors, facility managers, and building operators all strive to achieve exceptional performance from the mechanical systems and related equipment that make up the infrastructure of their buildings. A building automation system (BAS) is one of the keys to that performance, and a sequence of operation explains the job the BAS has to do. This article presents ASHRAE Guideline 36 as a tool to develop a sequence of operation.

Background on ASHRAE Guideline 36

ASHRAE Guideline 36, “High-Performance Sequences of Operation for HVAC Systems,” was published after a long series of projects by ASHRAE’s Technical Committee 1.4 Committee, “Control Theory and Applications.” It provides standardized HVAC control sequences with the goal of:

- Improving the quality of building automation by starting with a better specification;

- Conserving energy with HVAC-optimizing algorithms;

- Reducing engineering and commissioning time with standard functions;

- Solving technical challenges associated with diverse building operational goals;

- Improving building operation with smarter alarms and fault detection and diagnostics; and

- Creating a common language between specifiers, contractors, and operators.

The committee envisioned the guideline to be used in the following ways:

- Engineers specify sequence of operation using content right out of the guideline;

- Control manufacturers develop and test applications according to the guideline;

- Contractors apply proven solutions; and

- Commissioning agents execute standard tests.

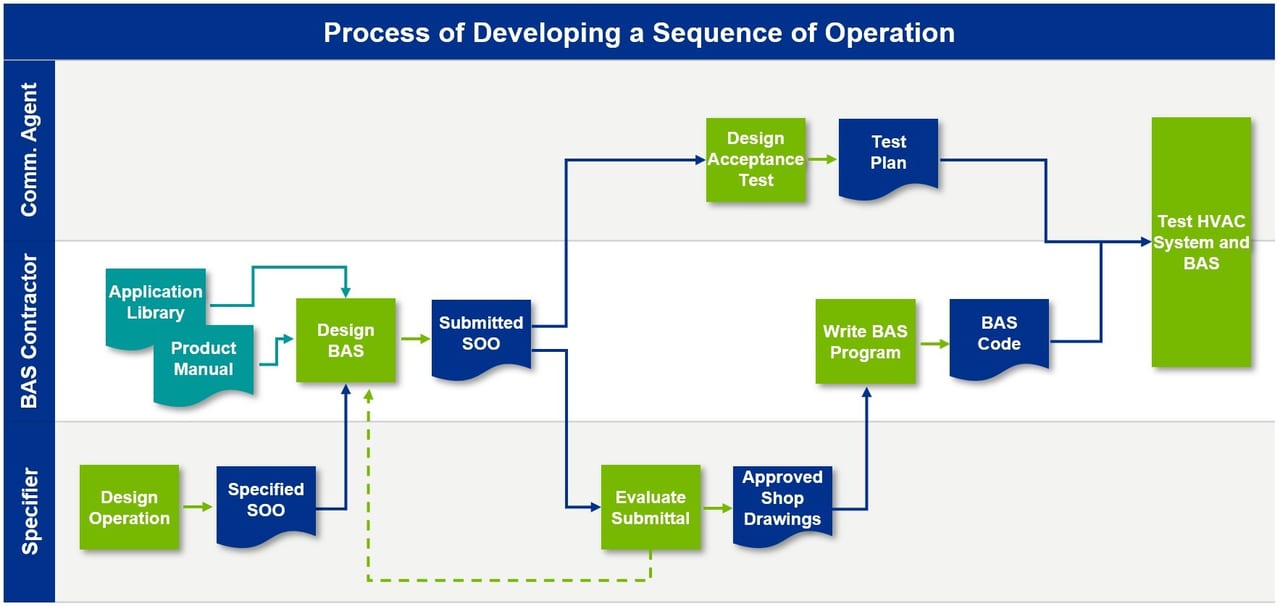

FIGURE 1: The process of developing a sequence of operation flow chart.

Finally, by utilizing ASHRAE Guideline 36’s sequence of operation, it makes it easy to comply with several industry requirements, including: ASHRAE Standard 90.1, “Energy Standard for Buildings;” ASHRAE Standard 62.1, “Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality;” ASHRAE Standard 55, “Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy;” ASHRAE Guideline 13, “Specifying Building Automation Systems;” and the California Energy Code’s Title 24.

Developing the Sequence of Operation for a Project

A sequence of operation describes the way the equipment in the building responds dynamically to changing demands. It is written out in construction documents and implemented in BAS software.

As seen in Figure 1, the sequence of operation originates with the specifying engineer. It is part of the project specification. It explains how the system should operate and be controlled based upon input received from the owner’s requirements, the architect’s layout, local and state codes, and the potential tenant’s needs.

The BAS contractor responds to the specification and designs the system. This includes identifying equipment and rewriting the sequence in terms more closely related to the products and programming libraries applied. The contractor submits this design for approval by the specifier. The specifier evaluates the submittal for conformance to the specification. If it satisfies the intent, he approves the design. If not, he rejects it, identifying discrepancies to be corrected. Here, there might be a cycle of give-and-take. The approved sequence might differ from the original description but must accomplish the same result for the building and its users. In such cases, the contractor needs to indicate how the design satisfies the design intent.

A Good Sequence of Operation

A good sequence of operation meets HVAC performance requirements for IAQ and comfort while conserving energy. It can include other areas as well, such as lighting and shade controls. It explains the technical operation of the equipment and system and can include features, like automatic fault detection, graphical displays, and reports for monitoring and maintenance. In addition to these technical requirements, the document explains the engineer’s design intent, which increases the chances of a successful construction project.

Observed Approaches to Applying Guideline 36

The following categories describe specifications for ASHRAE Guideline 36 projects being executed today.

Method No. 1: One General Reference to “Comply Guideline 36” — This is the easiest approach for specifying engineers, at least until the requests for information arrive. The specifier does not actually deliver a sequence that contractors and building owners can use. In fact, this approach shifts the specifiers’ work to contractors and commissioning agents, who each need to comb the guideline and identify the relevant passages. In the projects Siemens has executed, about 20% of the 2018 guideline version was applicable. Asking contractors to find that applicable 20% of passages leads to problems on the project.

This approach may become practical when use of the standard becomes routine. When manufacturers, contractors, commissioning agents, and owners are thoroughly familiar with the standard sequences, a single reference might work.

FIGURE 2: Cover of ASHRAE Guideline 36.

Method No. 2: Include Large Portions of the Guideline — Most of the text in the guideline was written for direct insertion into contract documents. Cutting from the guideline and pasting into a specification is intended and encouraged. The result is a project specification that stands alone, without reference to outside documents. It also grants the specifier the opportunity to tweak the sequence for special circumstances.

Some of the text in ASHRAE Guideline 36 is written to explain how the sequence is meant to function. Copying parts of that in the specification is unconventional, but it might be helpful.

Still another portion of the text is instructions to the specifier, such as “Designer, delete paragraph x or paragraph y, as applicable.” When the job specification includes paragraph x and paragraph y, and the instruction is to delete one of them, it looks like the designer did a sloppy job.

Method No. 3: Select Smaller, Specific Sections of the Guidelines — In contrast, a specifier can cut and paste in smaller increments. This method also results in a stand-alone document. It keeps the specifier in control of the design. It allows room to customize functions, though readers might not easily recognize what is standard and what is custom. Method No. 3 can be executed very well if the specification is written and edited carefully.

Method No. 4: Multiple References to Numbered Sections — A specifier can refer to passages of any size within the guideline. References, like, “Sequence the damper and reheat valve according to section 5.6.5,” or “The window switch affects room temperature set points as in 5.3.2.8,” work very well in a project specification because the specifier retains control of the structure, scope, and content of the project specification. He selects and applies standard functions, where appropriate, but can write custom features as well. It’s easy for readers to recognize what is standard, what is special, and exactly which passages of the guideline apply to the project.

All four of these approaches have been used on projects. Method No. 4 is usually the most likely to succeed on projects today.

Conclusion

ASHRAE Guideline 36 gives a specifying engineer a chance to deliver a better project specification but only if he pays attention to the details and communicates them to the project team. A better specification, and a standard specification, helps contractors and commissioning agents execute a better project. In the end, the result is a better building for owners and occupants.

Learn more on this topic through a recent webinar, “Improving Efficiency with ASHRAE Guideline 36,” courtesy of Siemens.

Jim Coogan

Jim Coogan is principal applications engineer, research and development, for building products at Siemens Smart Infrastructure USA. In 35 years of designing controls for mechanical systems, he has contributed to products ranging from room controllers to internet-based interfaces, resulting in numerous patents. He has chaired several ASHRAE committees, is a member of the committee currently revising the Z9.5 Laboratory Ventilation standard, and was voting member of the ASHRAE Guideline 36 committee. He participates in programs with the International Institute for Sustainable Labs, and his publications include technical papers on room pressurization and laboratory ventilation. Coogan earned his bachelor’s of science in mechanical engineering at MIT. Based in Chicago, he can be reached at jim.coogan@siemens.com.

[Geber86]/[E+] via Getty Images